Table of Contents

What You Will Do

- Explore the challenges and opportunities of urban settings.

- See a variety of strategies and case studies focused on urban food gardens.

- Recognize the importance of social justice issues and “invisible structures” in urban projects.

- Look beyond the garden at other opportunities to use ecological design in the city.

- Consider the connection between urban and rural communities, and determine where your project can help.

Whether you live in the city or in the country, the same tools apply

this section by Heather Jo Flores

This class was created mostly for our students who live in the city, but if you happen to live out of town, you will still benefit from the materials here. Regardless of your situation, all of the same design-mind tools we have been using so far can be applied: zones and sectors, microclimates, invisible structures, whole-systems design thinking, and the GOBRADIME Design Process are all just as valuable in a tiny urban space–even if you don’t own a place!

Applying ecological design in the city can be more complex than designing a rural home system, and one of the first obstacles many of us have to overcome is the lack of access to available land.

Access to Land

Although access to land for urban agriculture projects can be an obstacle, people have found a variety of creative ways to overcome this barrier. Here are some ideas to get you started:

Zones and Sectors in the City

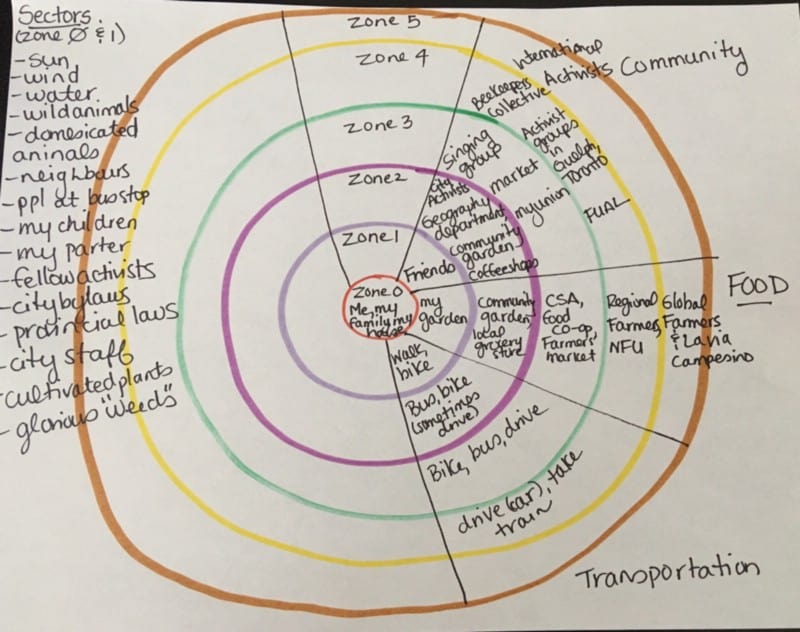

this section by Becky Ellis

When we think about applying our design skills to the city, we need to adjust the concept of zones and sectors to fit the scale, and realities of vibrant urban living. When I first started learning these skills, I continued to live in rented spaces in cities, with little or no access to my own space. I found it challenging to figure out how to design an ecological life without owning a large tract of land. This article is about how to think differently, on a city scale, about zones and sectors so that you can plan for a season of amazing urban design and practice whether it be in a small-space, no space, or community space!

Zones

The use of zones is a helpful way to organize our space and our lives so we can begin to design it regeneratively. It seeks to describe the intensity and frequency of use of varying spaces and is typically outlines as:

- zone 0 — you

- zone 1–the home and close-in garden, daily use.

- zone 2 — Orchards (also where small animals might live)

- zone 3 — pastures, larger livestock

- zone 4 — managed forests and wetlands

- zone 5 — the wild

In a city maybe it looks like this:

- Zone 0 — you and your home, chosen family (this includes kids, partners, close friends, lovers, etc)

- Zone 1 — Spaces used everyday (your yard, garden, possibly a park, maybe you go to a cafe or library everyday)

- Zone 2 — Spaces used 3–5 times a week (a community garden or community food forest, a coffeeshop, your workplace, perhaps your local library); often easily walkable, within reasonable cycling distance or on a direct transit route

- Zone 3 — Spaces visited about once a week (a farmer’s market, your CSA, a art studio where you take classes, maybe a park where you spend your weekend, a place where you volunteer, etc)

- Zone 4 — Spaces that you visit about once a month and/or that are important to your life but not a frequent part of it (a local organic farm, out of town friends or family, a managed park or conservation area, community organization mtgs). Also if you happen to regularly visit another city or country (even annually), I would include it here not in zone 5

- Zone 5 — The wild as well as parts of the world you may never visit but impact or are impacted by. I think it is crucially important to think about zone 5 to consider how our actions affect wild areas AND affect people throughout the world that who we may never meet in places we may never visit.

This can be played with to make it work for you. Once you have a sense of your zones, write them out using five concentric circles with zone 0 in the middle. I recommend making a diagram about your present life and a diagram about how you hope to redesign your life/spaces. You can divide the diagram into different sections such as food, outdoor spaces, community, and people.

Generally the most intensively and frequently used spaces as the ones that you develop first with your design plans. However, this doesn’t mean that you can or should only focus on yourself and your home. Many urban dwellers interact with our neighbourhood gathering spots every single day, so we need to give those areas our attention, time, and energy.

Sectors

Sectors are a design tool that helps you think about the different energies, sometimes thought of as ‘wild’ or uncontrollable energies, that make their way through your spaces. I recommend doing a sector analysis on zones 0, 1, and 2, if possible (you may have little control over some of the zones).

Energies typically considered:

- sun

- wind

- rain/water

- wild animals

- fire in some places

I also add human-created sectors:

- family members (including children)

- neighbours (including children)

- friends

- domesticated animals (yours or ones in the neighbourhood)

- city bylaws and staff

- community/activist organizations

- community ‘helpers’ (teachers, librarians, bus drivers, etc)

- businesses

- corporations

- ‘the public’ (the people in your city)

- OPPRESSION (how does racism, sexism, colonialism, class bigotry affect the energy of our spaces)

It is important to think of how these different energies, not directly controlled by you (even your children, let’s be honest), affect and use your spaces. They need to be considered when designing space. You need to know where the sun shines and at what time of day before planting gardens but you also need to know where your children like to play. These categories are not bound and they all interact with one another. In a city two crucially important and entangled sectors are city bylaws and neighbours.

It’s important to think about the flows of these energies not only the natural ones (wind, water, etc) but the human-created ones (children, domesticated animals). What energies flow in and out of your spaces and how can you design for and with them? Personally, I try to mostly think about how to work with these energies not to stop them. We might think we can block a meddling neighbour with a fence, but that is partly an illusion and might also block the flow of other energies (wild animals, for example).

Flexible, dynamic design

People can be rigid with how they use traditional tools and practices. Thinking through zones and sectors is an important design tool, helping you to uncover patterns and assisting in the visioning process that is so crucial to any good design. Use it in ways that help you and make sense for your life. Redo your zones and sectors regularly and think about what has changed and what has stayed the same (and WHY).

In my heart I am still a high school dropout who dislikes authority and rules so I need to state that these are guidelines not rules. Use zones and sectors in flexible ways to help create vibrant, regenerative urban spaces!

Questions to consider before you start a new urban project

this section by Jane Hayes

As we consider urban land projects, some of the first questions we ask in Toronto and the Greater Toronto Area around gaining access are:

- Is there a history of land use that has polluted the land (e.g. industrial use)?

- Who claims they are the legal “land owners”?

- Are there additional inherent rights holders, treaty holders, and/or other stewards of the land?

- What is the history and current status of the relationships that are playing out on and around the land?

- Who can we work with that is clearly and actively supportive to land-based projects and projects that reconcile or work with tensions around land relationships?

- What is the history, health and context of the land ecologically (e.g is it in a park, ravine, ecologically diverse area?

- Would working the land bring healing to a fragmented ecology?

These questions are some of what we consider when deciding whether to take on the work on a particular piece of land. We rarely choose simply because it is “ours” or very easy due to proximity to our houses, in part because we know we too will move on… thus there’s an important piece of work and questioning around who might have the long term capacity to steward the land over time and how we can design to support that.

Options for Renters

this section by Heather Jo Flores

If you live in the city, that doesn’t mean you can’t grow your own fruits and veggies! By using a few simple strategies, you can enjoy fresh homegrown fruits and veggies, year round.

If you’re renting, and especially if you live in an apartment, it might seem impossible to create your dream project where you are. But don’t be discouraged! The vast majority of our students AND our faculty are renters, and you can do A LOT without ever owning a place.

Gardening Tips for Renters & City Dwellers

Let’s get practical! It’s all fine and good to cultivate a designer’s mind, but we also want you to feel empowered to jump in and get dirty, no matter where you live now.

Here are some skills that will come in handy for every urban dweller who wants to grow their own food:

1. Master the art of container gardening. Container plants have their own special needs, but it’s a short learning curve and you can make containers out of just about anything, and place them just about anywhere, and get an abundance of food, flowers, and medicine. (We’ll circle back to this later on in the class.)

2. Grow your own worms. Worm compost makes a perfect addition to a container garden, and also gives you a handy place to dump your kitchen compost. A tiny worm farm is super fun to make and produces a large amount of fertility.

3. Growing in a small space? Grow small plants. Choose dwarf fruit trees and keep them pruned. Grow short-season vegetables and choose varieties that produce when plants are still small.

4. Maximize vertical opportunities. Grow edible vining plants like kiwi, grapes, passionfruit, or hops, and grow them up (and down) the sides of buildings, fences, and freeway overpasses. A tiny piece of ground can produce massive vines.

5. Meet the Neighbors. If you don’t have access to garden space, look around and see who does. Maybe they want to share, and you can grow food together. Or maybe your whole apartment building can rally the landlord and get a project happening on the roof!

6. Integrate with the existing landscape. Is there a local park? Maybe you can commandeer a sunny corner and start a neighborhood garden. Even a parking strip with some scrubby shrubs can be a good spot to plant a few zucchini or potatoes, and you might be surprised how much food you get!

7. Bridge the gap. Once in a while, if you can, hop on a bus, head out to a local organic farm, and do some volunteering. You will get immediate access to a community of humans who care deeply for the Earth and you may discover you have a lot more access to land than you realized!

How to bring social justice awareness to your urban projects

this section by Luiza Oliveira

Urban spaces are great hubs for innovation and the source of many social movements. Cities are meeting grounds and for creative collaborations, but can also be a place where social injustices and cultural paradoxes become very explicit.

There are many ways to look for access to land in the city. At the same time, it is important to understand that social injustices should be considered in the design of your project, so as not to reproduce or enhance dynamics of oppression.

How can you design a resilient, accessible and inclusive urban project that cares for the Earth and the People around it? Can you allow your private project to offer public benefit through thriving synergy, support and transformation within your neighborhood?

While you are developing your project and working through the goals, observations, and boundaries phases, begin to brainstorm actions you can take to create your local antidote facing common systemic problems. Then, design those actions into the plan in a tangible and replicable way.

Here are some examples:

Homelessness. A symptom of the colonial trauma, the marginalization, and dehumanization of people who for many reasons can not afford safe housing at that moment in their life. Be aware of what might look like a “vacant” space, you might find people and families living there.

Example Actions:

- Build an aspect into your project that provides a place for people to sleep at night.

- Talk with local homeless and ask them what they would like to see more of in the community. They may already have a place to sleep but wish for better access to fruit trees or garden space, for example.

- If you’re planning to do a “guerrilla” garden in a vacant lot, make sure it isn’t somebody’s home. You may be drawing law enforcement attention to a long-established campsite whose inhabitants might prefer not to be found.

- Connect directly with locals who do have housing and ask them to become involved in creating options for their houseless neighbors.

- Partner with affordable housing initiatives and housing coops projects in your neighborhood.

Gentrification. The process that dislocates traditional low-income residents (usually, BIPOC residents) changing the social fabric of the neighborhood. Gentrification is not about investments being made in an area, it is the result of the growing inequality due to capitalism. Gentrification is about the displacement of original residents, physical upgrading of most of the housing stock, and change of long-term community feeling around the neighborhood.

Example Actions:

- Include frequent dialogue with participants about what gentrification is and does, and work together to make sure your project doesn’t exacerbate the problem in the neighborhood where you are working.

- Host community story-sharing sessions and go out of your way to learn about the history of the area.

- Connect with existing groups and projects before starting your own.

- Organize a collective to focus on policy-making at the government level in your area.

- Turn your design project into a hub to create engagement around these subjects, and to support the social biodiversity of your neighborhood.

Cultural and structural racism. A remaining problem due to colonialism and slavery, creating many layers of social injustice. Many BIPOC struggles are related to residential segregation, healthy food apartheid, access to good quality health care, education, and jobs. White supremacy culture is reproduced in all levels of our society justifying and binding white-controlled institutions.

Example Actions:

- Work with yourself and your collaborators to challenge your own comfort levels around racism and racial awareness. Is it a trigger? Go towards the fear.

- Conduct a rigorous assessment of where your project might be unintentionally communicating a white-centered message. Are all of your images only of white people? Do all of your decision makers have light skin? These questions can be hard to ask, but our ethics make them necessary, especially if you are creating an urban project that includes the public. If internalized white supremacy sounds new to you, check out this text about it: White Supremacy Culture by Tema Okum.

- Find and partner with local BIPOC initiatives in your area. They are probably already doing some really cool projects.

- Hold space within your design, on an ongoing basis, to allow participants to give feedback, privately and confidentially, and respond to that feedback with curiosity, compassion, and changes to your program as needed.

- Invite any disgruntled participants from marginalized communities to help you create strategies that will allow you to work on your blind spots.

Tips for building inclusive projects:

- When looking for a space to start your project observe the space not only physically, as a place for your project, but also look at the social sectors that already exist around it, culturally and historically. Think about gender, race, class and how they shape the space. There is no such thing as a blank slate, especially in the city.

- Make sure when designing your project to integrate people from various backgrounds, and life experiences. Think about the people who have or not access to your activities, (physically and culturally) and how to integrate more diversity in it. Integrate and valuing intergenerational activities, multicultural spaces, welcoming marginalized folks, where BIPOC are celebrated, where all people feel welcome and cared for in it.

- Find creative ways to allow your design to become a hub where a thriving and colorful future for all people for many generations can celebrate and learn from one another.

- Care for the social-biodiversity of the cultural soil around your neighbourhood, looking for solutions to take care of each other, individually and collectively.

Like any design, your social systems should be site-specific, and should center the needs of the people and other species involved. For an amazing example of these ideas in action, look to Soul Fire in the city and check out the other examples in this class.

Case Studies and Examples

Here are a bunch of video and photo examples from different types of cities, demonstrating only a tiny sampling of what you can do.

Barcelona. In this video, Aline Van Moerbeke explores a few examples in Barcelona, Spain:

Correction: the 5.5 million inhabitants Aline mentions in the video are the people that live in the whole province of Barcelona. The city itself holds 1.6 million inhabitants. The larger metropolitan area has 3.4 people living in it.

Havana. Here Cynthia Espinosa Marrero gives a presentation about her experiences in Havana, Cuba.

Seattle. The Beacon Food Forest as an example of community sharing. They engaged in a collective process for many years, created a design, and made it happen. Here’s an inspiring map of their project:

Portland and Eugene, Oregon are both major hubs for eco-minded folks in the USA, but these cities are still a long way off from being sustainable, and the projects have often had the unintended consequences of accelerating gentrification. The City Repair project is a perfect example of how a group of folks can do amazing work but still cause harm in some areas because they don’t do well at considering the needs of all residents in a neighborhood. As you look for examples and inspiration, be careful not to allow yourself to get swept up in pretty ideals while accidentally marginalizing vulnerable people.

In the United Kingdom and most of Northern Europe, millions of people grow food in allotment gardens, which are similar to what we call “community gardens” in the USA, where gardeners lease a section of a large plot of land that is owned by the local government.

Detroit, Michigan. The Georgia Street Community Collective in Detroit is an excellent example of a community program that has really made the effort to connect with what stakeholders need and want.

Los Angeles. Even though LA is one of the least sustainable on the planet, the climate makes it super fun to grow food year-round, and lots of people are using gardening to help bridge gaps and build alliances.

Here’s an article from Devorah Brous about her work with inner-city families in in Los Angeles

New York City has thousands of gardens in public and private places all over the city. Even though the cost of living is extremely high and people struggle with extreme poverty and ongoing threats of violence on a level much more intense than most places, you can still find food, flowers, and sanctuary in every neighborhood. Here are a few quick examples:

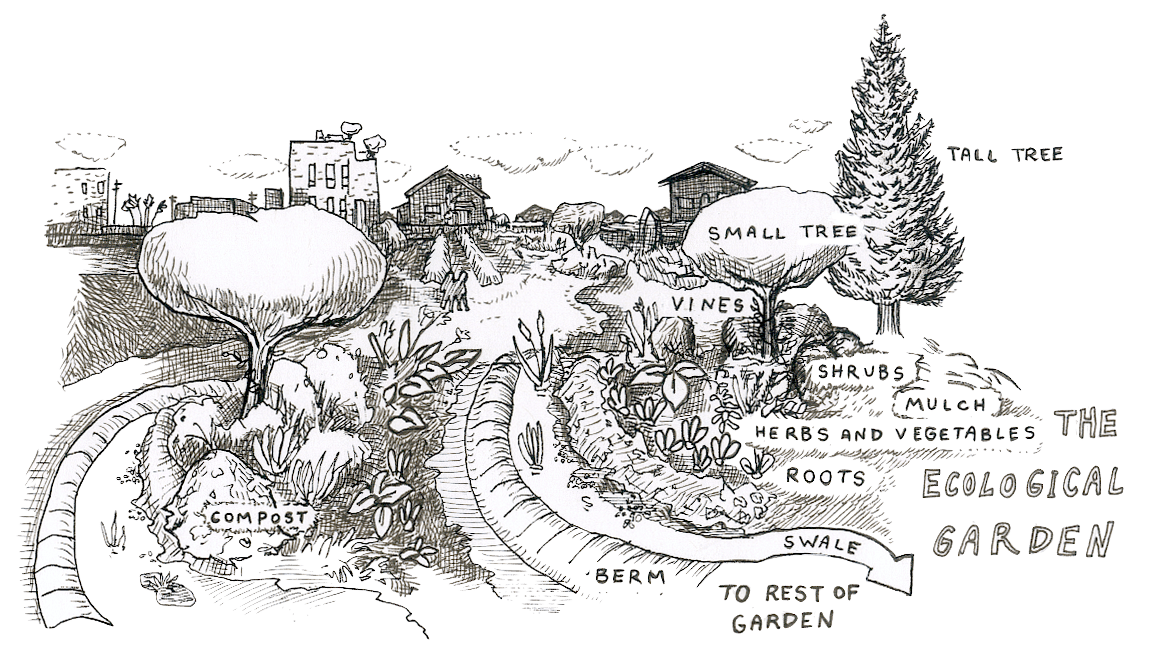

Urban Nature

Just because you live in a big crazy city doesn’t mean you can’t connect with nature. If you look, you may discover that it’s all around you! Whether in a local park, up on the roof, in a tiny alleyway you discover out on a walk…you can find opportunities to discover and learn from nature, and these moments, however tiny they may seem, will help you become a better designer.

Check out this video from Heather Jo Flores about edible and medicinal herbs and weeds you can find in most cities:

Beyond the garden: other types of pro-active urban projects

We’ve focused this module on gardening because access to land on which to grow food seems to be one the biggest obstacles our urban students face, but it is essential to remember that ecological design is about more than gardening…energy, transportation, education, economics, relationships, waste cycles, water cycles, built environment, zones and sectors–everything in a city is part of a system and ecological strategies can be applied across the board.

This video was created for our free beginner’s class, but it fits well here so we’ll pop it in for you! It briefly discusses ways to practice ecological design that aren’t really about gardening:

Homework

Questions for Review

- What sorts of community garden projects, right to the city movements, and the like are available where you live? Make an inventory and get involved!

- Do you have access to land? If so, would you consider sharing it? If not, how will you gain access?

- How will you foster healthy relationships with your neighbors, whether they agree with your ideals, or not?

- What other activities, besides gardening, will you incorporate into your urban projects?

Recommended Hands-On

- Include a layer of sector analysis that includes neighbors and other city influences.

- Map how you will incorporate neighbors, parks, and community gardens into your design.

- If your main design project is in a rural setting, include a consideration of the resources you bring to and from the city. If your main design is in an urban setting, include a consideration of how your project might impact or draw on areas and resources beyond the city.

- Find an urban gardening project and volunteer. Do whatever is needed but be sure to talk to people about their experiences while you work alongside them. .

- Find an experienced urban ecological designer and interview them about their experiences. Ask about their successes, the obstacles they encountered, and their advice for others. Pro tip: stack your functions and build relationships while you interview them by asking if you can record it. Share the recording and/or transcript back to them (there are softwares that can transcribe what was said easily).

- Get involved with a local community garden or urban agriculture project.

- If you live in a city, grow food in the pseudo-public spaces of your house and strike up a conversation with your neighbors about food production in cities.

- Look into establishing or being part of a sharing or bartering initiative.

- Join or support co-operatives and credit unions.