Table of Contents

What You Will Do

- Identify the needs and impacts of the animals on your site.

- Weigh the pros and cons of barnyard birds.

- Identify where wildlife are, and how they can be directed.

- Learn the basics of Integrated Pest Management.

Introduction and Inspiration

Here’s Liz Zorab with a full-system tour. Notice how her birds and animals are integrated with the system. Notice also that she is altogether unconcerned about insects, native birds, or any other critters “infesting” her garden. She is more concerned with making sure they have habitat and snacks!

Meeting Animal needs

This section by Kelda Lorax

Animals are parts of ecosystems

Within an ecological design framework, critters of all kinds, whether they are wild and pass through your site, or your own pets and livestock, fit into the greater ecology of the design in multiple ways. Some of these variables can be controlled by the designer, and some, of course, can not.

General tips to start with:

Put animals in habitat that makes sense for them.

Most poultry originate in forested ecologies or riparian areas. Most larger animals prefer savannahs where there’s enough light for grass, where yummy fruits and nuts just happen to fall from the sky, and enough trees for shade are around. Lucky for us, the most productive food forests are ones that have savannah-type (sparse and clumpy) canopy cover. If we put animals in there, and they’re pruning and pooping, then we’ve demonstrated the dynamic of everything gardens. And we’ve increased our yields.

Put animals with your plants.

If they do not cause harm to your plants, animals in gardens can eat pests, fertilize, gain nutrition (reducing your workload), and warn you of disturbances. This is a delicate dance to approach with seasonal caution, deterrence back-ups, and plan Bs.

Put plants with your animals.

It’s a sad pasture that provides no respite from the sun and wind. Luckily, trees are the answer. Figure out an implementation strategy (hint: use fences of some kind, or plant many years before animals arrive) and you can have a productive hedgerow, forage island, or savannah overstory that also benefits the animal tenants. A forage island is an area fenced from the animals that provide fruits and forages. The animals eat the fruit when it drops over the fence, or access the plants just at the fence line, but are not able to reach enough of the plant to completely destroy it. These areas can be shaped like actual islands (circular or lobed) or created by having two fences instead of one along borders (generally straight, called double fencing).

All animals need food, water, shelter, and space to be themselves. Whether you’re raising cows or edible grasshoppers, you should always assess how much time and materials their maintenance will require. This often means sharing responsibilities. Whether it’s a cow that’s milked by a whole neighborhood, or a big family that shares chores, always have a back-up plan for if you get sick (or if you want a vacation).

For any animal you plan to raise, you need to consider:

Food.

- What does the animal need to be healthy?

- What does it want to get into for treats, (so you can try to avoid too much of it)?

- What rotations and/or plants will provide much of their food?

- Where’s your best source for buying feed (if you need to)?

- Favorite forage plants for common livestock

Water

- How much do they need everyday?

- What delivery keeps the water cleanest?

- What will you do if it freezes in winter?

- What clean (metal) roof could you potentially catch water from?

- If your animals are paddocked, how much money/materials will you need to get water into each paddock?

Shelter

- How much space does each animal need?

- What’s their preferred way to sleep/lay eggs/be milked?

- What keeps the animal warm (i.e., wet birds can freeze to death more easily than dry birds, etc.)?

- Does the shelter move or is it stationary?

- Can your animal tolerate not having a shelter all the time?

Space

- What does your animal like to do?

- Could it be free-ranged/paddocked/mobile (remember that though all animals potentially could be free-ranged, your site may have limitations based on the need for animal work or the animal’s predilection to get into something it shouldn’t)?

- What types of structure will keep them where you want them?

- What type of structure will keep them safe from predators?

Waste

- How does the animal like to poop and do you want to utilize it?

- What ecological precautions should be taken?

- How will you process waste?

- Does their need to be a sacrifice area near the shelter, or a water source just to handle manure and avoid muddy feet problems?

- What materials might you need for this sacrifice area?

Companionship

- What companionship does your animal need?

- Could it be cross-species?

- What are signs of too much companionship (i.e. too much rooster abuse for your hens)?

Different ways to shepherd

The ancient wisdom of shepherdesses (to bunch the flock and keep it moving at just the right time) is akin to the modern fence. If you can spare a person with an excellently trained dog to handle livestock pulses, then you’re set. Otherwise, you’ll need to either

1) attract your animal to a mobile shelter that keeps it where you want in the landscape or

2) limit animal movement by a series of fenced paddocks.

Paddocks give your land the opportunity to rest as well as giving your animals the excitement of entering a fresh space loaded with food. They are important boundaries which allow for vital ecosystem processes.

Please read this for a good analogy comparing it to a dance hall.

This website shows a great image of how paddocks can be laid out in a large-scale system. Note that the fencing protecting the swales can also be called double fencing or forage islands.

The increased quality of life that paddocked animals experience on a regular basis, easily outweighs the fact that they have smaller fields to wander around.

Using animals as a restoration strategy.

It may seem counterintuitive, but if your site has been eroded, stripped of nutrients, or made barren for any reason, flushing animals through the system can help heal it. A little hoof action creates divots for water and nutrients to settle, manure adds nutrients, and if you feed the livestock the grain or crops that you’d eventually like to grow, some seeds are sure to be planted by the actions above.

A barren field could be planted with cover crops, and then pulse animals through. Or the livestock can help: The animals can be brought in with mobile fencing and shelter, and they can do the work of planting the cover crop. Both of these are great examples of the principle of using renewable services to share the workload that it doesn’t make sense for humans or machinery to do.

Meeting Wildlife Needs

Zone 5 isn’t just for wilderness, and wilderness isn’t just for Zone 5.

Bring an awareness into your designer’s mind about the wild creatures, big and small, that exist in nearly every niche of your design. Wildlife in your design shouldn’t be relegated to Zone 5 and forgotten. Wherever you are, there is wildlife there too!

Shepherding wildlife too

Animal influence is an important sector to consider. As you’ve been learning, many things can influence your site. Like the other sectors, animals coming into your design site can either be welcomed, redirected, or nothing can be done about it one way or the other.

Welcoming should be done for any number of beneficial species. Redirecting is often essential to avoid undue damage/impact to the species that help you meet your goals. Observation is encouraged before you form an opinion about how beneficial or harmful a species is. No matter what you’ve heard from others, how an animal behaves on your site may be totally different, for good or for ill. Observe and interact before making decisions.

For example, we had been warned about armadillos causing huge garden damage. But we’ve observed that once an armadillo arrived, it is very slow-moving and disinterested in our crops. Because we mulch heavily and have lots of forested areas, it is more interested in nosing into our mulched pathways and eating grubs under leaf piles. In short, it is aerating the soil and inviting in a dispersive pulse of disturbance that we consider beneficial overall.

On the other hand, we’ve done hours and hours of repair work to our gardens due to the damage caused by dogs, cats, and chickens (or dogs injuring or killing chickens). For these animals, time spent on calculating how they enter the garden sites, and how to deflect them from sensitive areas, is worth it. For our site, the dog sector is well worth spending time devising strategies for, whereas the armadillo sector is not. This demonstrates the importance of observation before design.

Here’s a key for Welcoming Wildlife

Start noticing wildlife around you, from tiny critters to birds and bees. Try seeing the world from their perspectives. What are their habitats? What do they do with their energy? What do they eat? What eats them? How can you protect their habitat and provide more places for them, or, if you want them to go away, how can you redirect them without hurting them?

Made for kids but seriously fun and educational for all ages, Wildlife Watch offers a collection of worksheets to help people learn about how to care for and cultivate wildlife wherever you go.

As designers, it’s essential that we think of how each of our sites can incorporate more habitat potential. Even an urban balcony or a parking lot can have mason bee homes, flowers, and water for wildlife. If we look at our site and say, “Ah, no wild areas, no Zone five, so be it”, we are severely disappointing our animal colleagues. No matter what other strategies we employ, we are letting the space/project down.

One useful way to think about zone five in non-traditional landscapes is to notice the shrubby, brushy areas that are naturally no-go zones for humans. It could be a shrub behind a dumpster, a place that’s awkwardly double fenced through various land uses, or even just an ornamental area that is never visited. During my travels in Ireland I learned that shrubby out-of-the-way places are left intentionally as a way to acknowledge the small folk who inhabit it. How can you do that on your site? If some tweaks can be made to the system, such as adding mulch or native plantings, how can you do that and stay hands-off from then on? Every site should have a zone five.

Pests, predators, and beneficial insects

No creature fits neatly into a category of always bad (a varmint!) or always good (a cute critter). As we watch the parade of wild species through an ecosystem, and seek to carve out space to feed ourselves, it’s helpful to think of ourselves as encouraging beneficial or much-loved wildlife closer to us, while discouraging undesirable activities. It’s of little use to blame the animal for being itself. Integrated Pest Management- The Smart Solution, is helpful in assessing threats by varmints and considering lifecycle weaknesses.

Create homes.

Think about the ecosystem as a collection of homes. Refer to the list of what animals need, and consider how you can create more habitat for wildlife in the landscape around you. Water sources like bird baths or ponds are strong invites. Changing aesthetics to let old plants linger through the winter provides homes for spiders, who are very important predators that keep your garden insects in check. Places in a landscape where plants can be thick and undisturbed are often the pathways and wildlife corridors, by which animals come and go.

Invite predators.

These are often scary-looking bugs like wasps, assassin bugs, praying mantis, ladybugs (don’t laugh, many a gardener has hated and killed their larvae mistakenly), lacewing, etc. They’re great news because they’ll scare and eat your garden pests, which often look fat, grubby, or have lovely disguises like cabbage moths. We want the ones that look like dragons to balance it out.

Encourage (Some) Parasites.

Yes, really! Certain adult insects won’t eat your garden pests, but their children will! These are predators but more gnarly. If you see something like the following image (tomato hornworm pest being parasitized by wasp cocoons), you might want to say a prayer for the hornworm, but be happy for your tomatoes.

Attract Pollinators.

This goes way beyond honeybees to native bees, flies, bats, beetles, hummingbirds, and more. Pollinators perform essential services in all terrestrial ecologies, and the protection of habitat that allows them to thrive is essential to life on this planet. Yes, read that sentence twice and take a moment to contemplate it. The Xerces Society, a premier conservation non-profit working on invertebrates, outline four simple steps to protect pollinators, that subsequently protect a lot of different kinds of critters too.

These steps are:

- Provide flowers and nectar sources. As varied as possible and with overlapping bloom-times to fully set out the buffet for a wide range of pollinators.

- Provide homes in your habitat areas. Homes for pollinators can just be untrimmed flower heads, piles of sticks, patches of bare soil, host plants and actual housing. A good rule of thumb as an ecological designer is to let your yard be a little wild and diverse and not over-managed. This is important! If that seems aesthetically disturbing, think about how your site can still feel well-kept to you while also being just right for the critters. These can be Zone four and five strategies that you don’t need to see every day.

- Don’t use pesticides. This is where all the other strategies come in handy! Unfortunately even organic (OMRI-listed) pesticides still occasionally impact non-target species, so focus on building up your site’s resiliency in other ways.

- Share and publicize what you’re doing, spread the word. Xerces has plaques for your garden and a pledge to sign online. The main point is that habitat works best in your yard when there’s plenty of habitat in the neighborhood and region. We need to work together as communities to protect pollinators.

Innovate deterrences.

This will be a mix of attracting an animal or activity to a different place, and scaring them slightly into going. It could mean making a varmint’s food prize just too annoying to access (think polycultures, thorny plants, scarecrows). It could be the smell of humans, or the barking of dogs, that make them uncomfortable.

Plan your wildlife corridor to direct animals away from precious gardens and plants, and have it full of its own fecundity. Animals do not intentionally set out to damage something you love. They may just need some direction.

Here are some examples:

- Assign a toddler the chore of chasing garden pests out of gardens. Give them a hose with a sprayer nozzle to make the point clear. Animals can be trained in this way. Plus it occupies the toddler, and waters the garden a little bit.

- Don’t totally clear or mow a site before planting. The brushy, tangly nature of scrub or pasture makes any fencing more effective. Deer will jump over fences clear on both sides, but they generally won’t want to walk through tangly bits to jump over a fence onto other tangly bits of an unknown nature.

- Know your pest’s daily schedules. If rabbits are feeling entitled to the garden early in the morning, by all means make them feel uncomfortable and start your day there. Likewise with slug hunting after dusk.

- Some treats that deter varmints elsewhere: Flowering buckwheat for deer, dry soil for pooping cats, compost piles for chickens, beer for slugs (although, anecdotally, it does seem to attract neighbor’s slugs onto your site, too), etc.

Beekeeping

Like many things in industrial society, the ancient art of beekeeping has been adapted to create the biggest yields, while propped up by chemicals and ephemeral transportation systems. And yet, bees are essential to our survival, and are recommended for gardeners who simply want pollinated plants.

Ways to think holistically about bee care:

Let them design it.

Bees naturally build hives in protected cavities and build their comb from an overhang down. Cell forms (plastic sheet with hive pattern) don’t let the bees build the size and variety of cells where they want them. Top Bar and Warre hives have gained popularity by just having a top bar that lets bees build their own cells. They spend more time making cells, and thus make less honey, but they’re often a healthier hive. Langstroth hives (the typical square boxes) can be adapted to this by simply not using cell forms. I like to think of this strategy as one of Masanobu Fukuoka’s general queries: What can we not do?

Whose honey is it?

Bees make honey to ensure survival of the hive through the winter. This should be the biggest consideration before humans harvest honey for themselves. The standard treatment is to feed them sugar water after robbing the hive, but this leads to weakness. This is part of the “perfect storm,” contributing to Colony Collapse Disorder (i.e. a reduction in bee populations.)

Of course, local honey is healthier than sugar imports from far-away lands, so I do advocate robbing honey. As designers, or harvesters of any natural resource, we should strive to do so when conditions are right and we don’t compromise the health of the system. An easy way to do this with honey is to only harvest it at the right time (you’ll need to talk to locals), from only very healthy hives, and to err on the side of less honey for you, but more for the bees (an earlier harvest than commercial operations.) It’s also helpful to remember it’s called “robbing honey” for a reason. Give gifts for your bees after this period to help them recover, like planned abundant bloom times.

Keep the hive healthy.

Robbed honey, incorrect cell size, pesticides, chemical use, climate change, lack of nectar sources, varroa mites, disturbance from humans in the hive box, and a host of other things lead to colony collapse. Our job as beekeepers is to decrease harm to them in whatever way we can. As gardeners we can ensure bees have nectar sources, non-toxic gardens, medicinal oil-producing plants (like oregano), and clean water sources. All of these small efforts add up to healthier hives, though that may also mean losing hives that are not strong enough. It’s good to think of your site as practicing proper bee hygiene by minimizing pesticide drift, for example. What would you want if you were a bee trying to keep your hive immunity strong?

Please read this article which summarizes the main types of beehives.

Pros and Cons of Barnyard Birds

This section by Heather Jo Flores

Barnyard birds add character and entertainment to the home system, eat weeds and slugs, and sift and manure our leaf-mulch for us before we add it to the garden beds. Interacting with these and the other animals on our farm brings us closer to nature and brings our farm closer to a closed-loop fertility cycle.

However, if we try to add birds to a site, with big fantasies about all the abundance they bring, but without integrating serious considerations for the time, money, and other inputs those birds require, disaster and disappointment could easily ensue.

Adding domestic birds to a garden, whether urban or rural, brings in life, fertility, and beauty. These benefits can help bring an average garden closer to paradise, but they are sometimes offset by the (often unforeseen) difficulties with these birds. Birds are smelly and dusty, and even a small flock will ruin a nice garden within a few minutes, given the opportunity. Here’s an overview to help you decide.

Chickens

Pros

Comfortable in a small coop or “chicken tractor.” Steady flow of eggs. They will weed an established perennial garden or spread mulch. They are tameable, trainable, and quite smart.

Cons

Very noisy! And not just the roosters! Even the hens, from dawn to dusk, all day, every day. They scratch up baby plants if let loose in a young garden. Easily killed by natural predators.

Ducks

Pros

They eat slugs and snails. Eggs are big and delicious. Ducks are funny to watch and quite sociable, and they come in at least as many varieties as chickens.

Cons

Ducks are fairly stupid, so it can be difficult to get them to go where you want. They love to eat salad and will trash your garden badly. It also bears mentioning that male ducks are prone to gang-raping females. So, there’s that.

Here’s a case study from faculty member Lydia Silva, about how she incorporates her chickens and ducks into her whole system design in rural Massachussetts.

Geese

Pros

Beautiful, graceful birds, geese are my favorite. The young goslings are very easy to tame. Goose eggs are edible and very rich, and the hard shells last forever when painted.

Cons

They poop a LOT, so if they’re free-range, it can get nasty real fast. They can also be aggressive if not handled when young and they will bite you—hard!

Turkeys

Pros

Delicious and nutritious, and you get a lot of meat from each bird. You also get tons of gorgeous feathers, even if your turkeys are just for pets and insect control.

Cons

Turkeys are huge and make a lot of poop in barnyard setting. They can be aggressive, can fly, and will go feral if you let them. They will chase children and demolish the garden. Not recommended for small holdings.

Guinea Fowl

Pros

Great meat birds because, at four months old, they can weigh several pounds. Baby chicks are sweet and adorable and make cute noises, but…

Cons

. . . grown guinea fowl make a hellish screeching sound similar to that of a busted fan belt on a car, and they will sustain it for hours.

Pheasants

Pros

Stunningly beautiful, very wild, relatively low-impact when left loose in the garden because they prefer bugs to plants.

Cons

They often run away, and male pheasants can be very violent (read: rape-y) towards chickens and other birds.

Quail

Pros

Said to be delicious, though I can’t see how such a small morsel could be worth the trouble. Their call is sweet and super cute.

Cons

Impossible to tame and so tiny that they usually run away or get eaten by predators. Build quail habitat in your zone 4, but don’t bother trying to cage them.

Chukars

Pros

Similar to quail but larger and more beautiful, with a wonderful call. Chukars are lovely in a garden setting and can live well with chickens.

Cons

Like quail and pheasants, chukars will not put eggs on your table. Unless you plan to eat them, they are just for looks and insect control.

Pigeons

Pros

Great poop; very compatible with a small garden setting. Beautiful and interesting to listen to.

Cons

They can breed like rabbits and will often move into an area where you don’t want them.

Peacocks

Pros

Fabulous in so many ways—who doesn’t love the idea of peacocks drifting about the yard? The feathers are valuable for many uses, and they will breed readily, given enough room.

Cons

Again, very difficult to tame—our peacocks went feral and live high in the conifers on the outskirts of our farm. We hear their calls in the sunset…

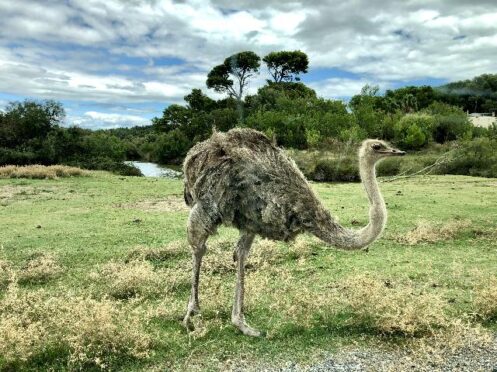

Emu

Pros

Even more fabulous, and highly prized for their feathers, meat, and oil. Easily adapted to temperate climates and very tameable.

Cons

Untamed emus can be vicious and, since they have claws like a velociraptor, they could easily kill a dog or human. Get them young and treat them right to make sure they aren’t dangerous.

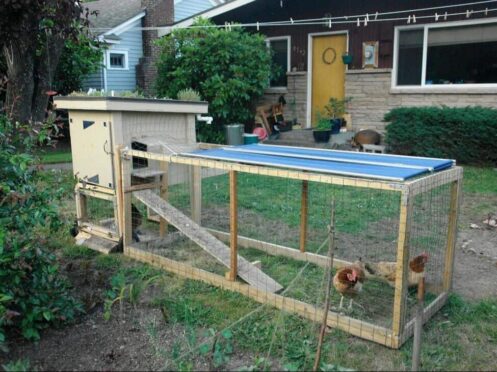

The Chicken Tractor

This section by Marit Parker

Free range chickens are a joy to behold – until they turn your seed bed into a dust bowl, hide the eggs in a thorny thicket and get eaten by a fox. However, shutting them in a permanent run means your chickens will be scratching the same bare earth every day. Meanwhile, your veg bed has pests they could be eating.

One solution is the chicken tractor – a moveable chicken coop and run. If you make one yourself you can design it to:

- Suit the number of chickens you have

- Fit over your veg beds

- Move easily around other parts of the garden

For happy chickens, you need to think about what chickens need. Their wild ancestors, the red jungle fowl, roost in trees, which is why chickens like having perches to roost on in the coop and enough space in the run to stretch their wings. Hens like having nesting boxes where they can hide away to lay eggs.

For happy humans, you need to think about how the chicken tractor will be moved, and have easy access for cleaning the coop, feeding the chickens and collecting the eggs.

Here are a couple of examples:

This design, made from off-cuts of wood, is quite heavy so it has wheels at one end. The mesh floor of the coop is a clever idea, but in some climates a wooden floor is needed to protect the chickens from cold winds and driving rain.

Alternatively, it is possible to make a lightweight version using plastic pipe. However, be aware that this is not as sturdy and may leave your chickens exposed to attack by dogs or predators.

Case Study: Kim Deans shares how her “chooks” and cows are a part of her whole system design.

Including Livestock

This section by Marit Parker.

Starting with livestock is a big decision so remember that you don’t have to jump straight in and start breeding straight away.There are ways of having a go first:

- Buy in a few young animals to rear and fatten.

- Try out different breeds.

And don’t rush! Give yourself time to learn and gain experience looking after one type of animal before starting with another type of animal.

Sheep

One of the first decisions you have to make if you are starting with sheep is which breed of sheep to go for. And that will depend partly on the type of land you have and the climate, as some breeds of sheep are more hardy than others. Hill and mountain sheep are hardy animals that can survive out in harsh conditions all year round. Lowland sheep need better pasture and some shelter. It will also depend on your reason for keeping sheep. Sheep produce wool, meat, milk – and more sheep!

All sheep grow wool, but some grow finer wool than others. If wool is your main reason for keeping sheep, it is worth talking to spinners and weavers and also visiting agricultural shows, especially if there are rare breeds of sheep competing.

Did you know that sheep are matriarchal? Take a moment to take in this beautiful story about sharing the leadership role with a ewe.

All sheep can provide meat, but some grow to bigger weights than others, and the flavour of meat from different breeds varies quite a lot. Think about who the meat is for. Is it just for your family? Or are you hoping to sell it?

All sheep produce milk for their lambs. A select few breeds can also be milked, usually for making cheese. Manchego for example is made from sheep’s milk, and traditionally so was Wensleydale cheese.

Even if wool isn’t your primary reason for keeping sheep, your sheep will need to be sheared every year for their own health and comfort. However, because nylon (ie plastic) is more popular for clothes, blankets and carpets, the value of run-of-the-mill fleeces is less than the cost of shearing them. So wool has become a waste product, instead of being valued for its warmth and its breathability, and the fact it doesn’t pollute the environment with microplastics. Time to close the circle and change back to wool!

Take a look at Shepherdess Lesley Perrett’s YouTube channel where she demonstrates practical skills needed for looking after sheep.

And when it’s time for lambing, check out my article here.

Cows

Cows, being bigger animals, need more space than sheep. However, they fit well with sheep in a system because cows eat long grass, whereas sheep eat short grass, so sheep can follow cows in the rotation system.

These days, cattle are divided into beef breeds and dairy breeds, but most older breeds are dual purpose. If you are thinking of having a house cow, then a dual purpose breed makes sense because in order to produce milk, a cow needs to have a calf. And you want both good milk and a calf you can eventually have beef from.

Cows are getting a lot of bad press these days and getting blamed for climate change. In fact, any carbon or methane they produce is part of the natural carbon cycle, just like the CO2 we breathe out.

Cows haven’t dug up fossil fuels to create it! Cattle reared on pasture play an important role in maintaining the biodiversity of the meadow, and in ensuring the soil continues to store carbon.

Goats

Goats are browsers, not grazers, which means they prefer eating trees and shrubs to grass. They are also agile and can jump and climb, so good fencing is crucial. A herd of goats can destroy an orchard in a matter of minutes. They can also clear acres of brambles in a matter of days. Design makes the difference.

Here are 21 other things you need to know about goats.

Alpacas

If you’re at all considering bringing these smart, gorgeous, and hilarious animals into your system, check out this lovely article/personal case study.

Rabbits

Some folks keep rabbits for manure, meat, and weed control. They’re easy, quiet, and don’t take up a ton of space, though it’s hard to keep them free-range because they are quickly stolen by raptors, so you end up having to keep them in cages, which might not be preferable for some designers.

Intensive grazing systems

this section by Kelda Lorax

Though it goes by many names, the rule of thumb for ecological livestock-keeping often involves moving the animals in groups that mimic how animals clump together when threatened by predators. The action of such groups (whether it’s geese or bison) is to hit an area hard, eat copiously, disturb the earth, poop, and move on. This is stimulating to soil systems and plants, and the flush of growth that happens during the rest period creates a lush healthy meal for the next eaters in the system. This strategy has been widely popularized by Allan Savory’s Holistic Management, and now has a growing pool of research testifying to its scientific credibility.

Know your brittleness.

Some landscapes can thrive with occasional disruption. These are usually landscapes with plenty of moisture where nutrients are available to growing plants. Other landscapes, that tend to be drier and more brittle, heal more slowly from disruption, and can be caught in a cycle where disruption leads to the inability to heal. How often animals are pulsed through a landscape is dependent on these factors. Animal herds can heal very brittle landscapes (through hoof prints, manure deposits, etc.) and herds can also injure very non-brittle landscapes, it just depends on timing.

Know your rotation.

The art of pasture rotation (which cannot be taught completely within the confines of this class) is dependent on knowing your pasture species, growth season, rainfall patterns, and specifics of the livestock species involved. Animals left too long in an area will eat to death their favorite plants and let weeds grow (i.e., overgraze). However, it takes fencing (money) or time to move them constantly. You’ll need to find your balance.

Pets in the system

Do you have pets in your home system? Don’t forget to consider them in your design! Dogs can help keep deer out of the garden. Cats will kill rodents but will also kill lots of birds and lizards. Pet poo can be composted, but you should do some research first. Pets have inputs and outputs just like everything else, so we just wanted to include a little note here to remind you!

Homework

Questions for Review

Note to apartment dwellers or those who don’t necessarily have a lot of land to work with: imagine that the rooftop and whole footprint of the housing development or nearby green space (any outdoor sitting area, parking lot) is available for you to design as you go through the following questions:

- If you were to keep some kind of bees at your site, which would you choose and what style of home or hive? (Langstroth, Top Bar, Warre, Clay, Basket, etc.) If you already have bees, what can be improved?

- If you were to keep some kind of poultry at your site, which would you choose and what style of design and shelter? (Coop and run, mobile coop, paddock shift, free range, etc.) If you already have poultry, what can be improved?

- If you were to keep some kind of large livestock at your site (or nearby), which would you choose and what style of design and shelter? (Type of mobile shelter, fencing type, etc.) If you own livestock, what can be improved?

- Identify a wildlife habitat strategy you can add to your site, and name three additional local species that may be attracted to it.

- Name a troublesome wildlife varmint to your site and how a holistic ecological strategy could decrease its negative impact.

- Identify where in your site design you can include zone 5 “biotopes”. Even in a small space they could be a window box of bee and butterfly forage plants for local visitors, a bee hotel on a windowsill or a safe space for spiders to weave webs and provide fly catching services.

Recommended Hands-On

- Make a list of the birds, insects, and animals that populate your site. Learn about their habits and their habitats, learn what they take, and learn what they give.

- Map the animal space, patterns, and flows on your site. Identify which zones which animals are a part of, and why.

- Create places where visitors can interact with your animals, beehives, or barnyard birds, and demonstrate the way they integrate with your whole system design.

- Include forage, habitat, pollinator gardens, and related components to encourage a healthy biodiversity in your design.

- Find and visit local farms that raise the kind of livestock you’re interested in. The possibilities are endless for hands-on work with livestock. And it is certainly hands on!! Volunteer to help, and learn how to milk cows/goats, harvest honey, etc.

Make a mason bee home!

They can be created in two general ways:

1. By drilling into a block of wood or making non-toxic paper tubes. They are solitary bees which overwinter in holes packed up with mud. They are excellent native bee pollinators appropriate for any garden.As you assess what tools and materials you have available, know that the drilled holes or tubes need to be 6” long and just wide enough to fit a #2 pencil. Materials should be non-toxic (no treated woods or dyed paper), and the whole structure should be sheltered from rain, stable enough to survive heavy winds, and somewhere eastern-facing or sunny (though not too sunny in hot climates.)

A good overview of the block method here.(you can also use parts of downed trees or thick branches)

2. Or, try the straw method here.

(you can also use hollow plants like elderberry or reeds)

Find an extensive annotated bibliography, on topics covered here, from beekeeping to pasture management, from vegan animal tending to welcoming wildlife, with topics sorted by type of animal or practice, in the full-course resource list, here.